Press Articles

Gordon Froud's Retrospective of Exhibitions I Never Had

In David Paton's opening ganbit for Gordon Froud's Retrospective of Exhibitions I never Had, he describes the exhibition as "evidence of a thinking mind made visible through a thinking hand" with "content which, while never having been polite, never having been without its wry and often black wit, reimagines a deeper, bleaker, edgier, more critical world." The Art Times caught up with Froud to shed some light on the exhibition, which promises to be a prominent feature at the KKNK this year.

Foto: Brendan Croft

G'n prestasie in isolasie, sê speelse 'Aard-varke'

Gordon Froud is die skepper van vanjaar se Aartvark-trofee vir grensverskuiwende werk op die Aardklop-kunstefees. Dié fees begin Maandag in Potchefstroom. Die gesogte Aartvark-prys word deur Beeld se Kuns-en-vermaak-blad toegeken. Getrou aan Froud se speelse benadering benadruk hy met sy aluminium-beeldhouwerk die vark in Aartvark deur vyf varke opeen te stapel. “Hoewel die boonste vark die kleinste is, is hy nietemin die top dog, dié een wat met vindingrykheid en vernuf die boonste sport bereik het,” sê Froud van sy beeld. ’n Element wat verder in dié beeld duidelik na vore kom, is dat ’n kunstenaar, hoe goed hy of sy ook al mag wees, bou op die werk wat kunstenaars voorheen vermag het. Geen prestasie staan derhalwe in isolasie nie. Benewens kunstenaar, is Froud kurator, beoordelaar vir talle kunskompetisies en kunsdosent. Kortweg kan ’n mens hom beskryf as Meneer Kuns. Sy kennis van die hedendaagse Suid-Afrikaanse kunswêreld (onder meer) is verbysterend. Soos dit ook blyk in die Aartvark-werk gebruik Froud meermale modulêre komponente wat herhaal word. Dis juis in die herhaling van die onderdele dat hy daarin slaag om ’n nuwe geheel te vorm. Die Aartvark-prys is nie vir die beste produksie nie en word slegs toegeken aan iets wat op Aardklop debuteer. Die Aartvark-paneel kyk na alle aspekte van die kunste – tentoonstellings, straatgebeurtenisse, plakkate, produksies, akteurs, regisseurs, ontwerpers en choreograwe. Die kernwoord is grensverskuiwend, die prys gaan dus aan ’n kunstenaar wat verandering teweegbring binne die bestaande kunste-orde.

Map: Solo exhibition at Harrie's Pancakes Pretoria

To say that Gordon Froud is continuously toying with ideas would be no lie. Perhaps not only with ideas, but also with materials, form and meaning; or, in terms of his research project for his Master’s degree, with modularity, repetition and meaning. In any description of Froud’s work, the notion of toying – or playfulness, quirkiness, an odd sense of humour – comes into play. In 2000 his toying – at that time with disposable crockery and cutlery – led to a well-received exhibition in Paris while he was a resident of the Cité International des Arts. The next year he elaborated on this concept when he exhibited Plastic by Nature at the Open Window in Pretoria, a show conjuring a Legoland created out of white plastic plates, cups, bowls, knives, forks, spoons and other disposables. With these two shows, Froud the “playful engineer” made his mark through an innovative use of found objects. Download Gordon Froud: Map Catalogue

Set My Chickens Free! or, the meaning within the banal of Gordon Froud

'Lost and Found', Gordon Froud's exhibition at the art.b, features an installation of a large number of small-scale sculptures made from found objects (mostly cheap plastic or wooden toys) that have been conjoined, or cast in bronze or aluminium. This exhibition is the first to be organised by the newly appointed curator of the gallery, Guy Willoughby. In addition, the exhibition presents photographs and paintings by his collaborator Carla Crafford. Apart from the sculptures, an edition of three catalogues (or rather artist's books), containing a sculpture and a large series of photographs of Froud's works by Crafford, is also available. This catalogue shows an impressive body of work by an artist that has been prolific for some time.

Abstract fairy tale exhibition makes an ephemeral statement

Exhibition: Plastic by Nature Gallery: African Window

It often happens in postmodern art that an installation of some kind or another is erected, with no beauty or integrity of its own, and being totally dependent on some or other symbolic meaning outside the work itself, which no spectator could reasonably have been expected to arrive at without verbal explanation from the artist, which often indeed accompanies the work in some form or another. In the case of Froud’s plastic installations, though, the opposite is true: one does not need an explanation of any kind. The moment the spectator enters the dark, cold, cave-like gallery, he is immediately completely overwhelmed by the variation of abstract forms, reminiscent of plants, stalactites, stars, altars, clouds, snowflakes and space shuttles: a whole abstract fairy tale world, created out of light and mostly white plastic plates, cups, bowls, knives, forks, spoons and other junk, unaltered except by the combination of the artist had arranged them. One is touched by the artist’s almost incidental statement to a news reporter that, instead of receiving a single penny for this exhibition, and despite the sponsors on which he depended, he had to pay in R 10 000 to be able to hold this exhibition, in order to give the world a message that it needed quite desperately. With this action he is, perhaps unknowingly, reversing the values of insatiable capitalist society, always wanting something new with which they immediately get bored the moment it has been acquired, only to throw it away, turning it into junk that pollutes the earth and after which an immediately new effort is started to acquire yet something newer and more inaccessible. Furthermore, the ephemeral nature of this exhibition, which, at the end will be broken up into thousands of plastic utensils, cups and bowls from which it was made, and once again be used by people, makes it impossible for anyone to acquire any works from the exhibition, thereby fulfilling the definition of an aesthetic experience of something beautiful without the desire to necessarily acquire the specific beautiful object. At the same time it frustrates the ongoing urge of the capitalist consumer who simply wants everything he sees, as well as turning the whole exhibition into a small, ephemeral and wonderful, almost religious ritual in space and time. If only more people would have been willing to listen to artists like this one, it might have been possible to save a decadent western civilization on the edge of self-destruction by sheer imagination, beauty and power of the creative soul. A Look Away, Issue 10, Quarter I 2008 Gordon Froud

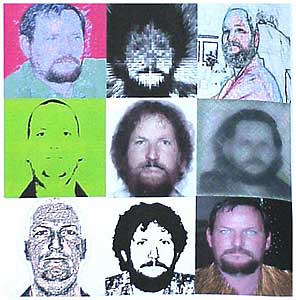

Gordon Froud creates sculpture through the strategies of modular construction and repetition. Or to put it another way: the sculptural form expands by virtue of his obsessive repetition of constructed modules until the final pies becomes the sum o f its parts. So the raison d’être of Froud’s artistic production resides not in what the work narrates or represent but rather in the visual record of its making. Art works of this nature are self referential or self-reflexive, they operate out of a system of circular logic and, to a large extent, are neither impacted on by their surroundings, nor do they seek to comment on their surroundings, The jus are. Or so it would seem. It is interesting that this mode of sculptural construction, which can be considered to have had its earliest manifestation in Andy Warhol’s multiples of the 1960s – but more realistically in Tony Cragg’s work of the late 70s – is now considered to be Postmodern strategy. It could be argued that its loyalties lie more comfortably within the Modernist idiom that sought to create a pure, universal language that spoke of nothing outside of itself – “art for art’s sake”. And yet is more complex that that. Contemporary American artist Tom Freidman describes his approach as a process of scrutinising his proposed material to decide what it may stand for and what his experience of it is, before devising a way of breaking this material down in such a way that the viewer is obliged to look at each piece in isolation in order to construct the total image meaningfully (2001: 11)¹. So even while the final object may remain mute, the creation thereof becomes a metaphor for the artist’s thoughts or intentions. Froud is fully aware that his work triggers extrinsic response but he is at pains to keep this kind of metaphorical assessment of his work to a minimum. So although the objects used to construct the basic building block cannot but retain an element of their original signification, especially in view of the fact that Froud makes no attempt to disguise them. Froud subverts or attenuates this meaning in the act of the sculpture’s making. Obsessive repetition of the module allows for the transformation and reclassification of the original elements, as does the selection of “unusual” materials. Coat hangers, plastic buckets and cheap plastic dinner plates are stacked, joined and clustered in ways that alter their usual context and re-present them as disinterested building blocks. This process of obfuscation is further intensified in the act of looking: as the viewer plumbs the endoskeleton of the work, units are dismembered, reduced to their basest elements, even atomised in the process of understanding and appreciating the sculpture’s structure. Only then does an intellectual reassembly of the work take place’ by which time the original content of the omnipotent parts has been sabotaged. Furthermore, as these seemingly commonplace building blocks are placed within the context of a commercially available artwork in a bona fide gallery space, their meaning and worth are altered and elevated irrevocably so that both the overall sculpture and its component parts begin to resonate on multiple levels. On Modularity: Artist who work with modular construction do not conceive of their materials as something pliable form which form can be coaxed through the techniques of modelling, casting or carving. Instead they are struck by the potential of already extant objects with which to build new forms. In so doing, the pioneers of modular construction ensured that not only did the surface cease to be the be all and end all of art, but that individual modules visible in the core of the work become the conceptual elements on which meaning hinges. Generally speaking, modular construction is also not concerned with the shape of the final form achieved. In fact Richard Storr (2001:118) suggests that the success of a work thus constructed relies less on overall shape – which is often impossible to hold in mind because one’s eye penetrates the interior - than on the principle of construction visible within, which is much easier to grasp. Therefore a typical modular approach suggests that once the material and structure of the building block has been determined by the artist, it is “left to it own device’ to direct and dictate the eventual form by virtue of its physical properties. Froud has chosen to adopt a different tack however. Instead of allowing individual modules to dictate the final sculpture’s form, he has set himself up to create only circular and spherical structures. Why? One might ask. Froud is adamant that he wants his work to be read primarily in terms of its modularity, its repetition of forms, and the material chosen. He has specifically shied away from narrative or figurative content and states that if there is to be an extrinsic interpretation of the work, then this must be secondary. He has based his choice of sculptural form on an idea offered by Tony Cragg who writes that “In some sense a sphere is the most useless of all forms, due to its super symmetry and extreme economy of surface it has the tendency not to react with other forms around it” (2006:192)². In response to this, Froud contends that he finds the sphere’s symmetry and surface economy underpin the “neutrality” or lack of signification of a sphere, therefore suggesting it as the ideal form with which to work. On repetition Repetition is necessarily an integral part of modularity since without it; the new form could not grow. But repetition becomes a more interesting strategy when analysed from the point of view of what it might signify. It could be about the artist’s closer and closer scrutiny of something rather like looking at the molecular structure of the object. Early on in his experimentation with the potential of plastic coat hangers as modules, Froud created a spherical structure with radiating projections. Ignoring the obvious external associations between the star like shape of the piece and a hugely magnified snowflake for a moment, this is an important example with which to gain a further understanding of how the repetition of modules contributes to a self-reflexive text and intrinsic meaning. Coat hangers are triangular and flat, which allows them to be joined together to form pyramidal forms, which can then be joined to form tow-dimensional lattices or three dimensional crystal lattices. Ice, the basic building block of a snowflake, also follows a crystal lattice structure. So rather than interpreting this piece solely in terms of the direct representation of a snowflake, on is able to go a step further and read the work as text for the snowflake’s internal structure. On material choice: Since Froud has opted to create only circular or spherical sculptures in this body of work, his endeavours become inescapably more complicated. He can no longer rely on the inherent physical properties of his units and must instead “artificially” manipulate them, forcing them to conform to his preconceived vision. He can approach this problem in two ways: either he must continue his choice of objects to those that tend towards a circular curve or form, or eh must construct original modules that will do the same. He has had success with many disparate objects such as kitchen utensils, audio cassette tapes and plastic champagne glasses in the former quest but it is his modules constructed from plastic coat hangers that have offered the greatest technical challenge and possibly as a consequence, present the greatest potential for success. Coat hangers pose a number of problems for one they are basically flat and therefore do not naturally lend themselves to three-dimensional construction. Secondly they are light and flimsy with low tensile strength but quickly become astoundingly heavy when massed. On the upside however is their roughly triangular shape which allows them to be joined together to imitate patterns found in nature. In addition to the snowflake example cited above, Froud has also explored hexagonal and pentagonal modules. When joined together, these more complex modules begin to describe a curve, an hence the beginnings of as sphere. Froud is well versed with the challenges of modular sculpture and admits to having been tempted to resort to an internal armature to hold the bigger structures together. But he has avoided this as far as possible since had he not, the internal language of signification of the units would have been disrupted. The module should be both physically and intellectually integral to the structure. In conclusion: In a Postmodern environment one might expect the solipsistic nature of modularly constructed art to be rather hurriedly passed over in favour of something more conceptually or metaphorically meaningful, after all, the objectives of Modernism seem rather idealistic and irrelevant now. And yet this is most certainly not the case, so what is ait about this kind of work that still holds our attention? I would argue that in an age where mass production and convenience dictate our every material desire, we nevertheless have not lost our appreciation, and indeed our need, to be motivated by something “greater than ourselves”. We still need to feel a sense of awe when we contemplate the tenacity, single-minded purpose and skill characteristic of much modular sculpture. Also, most modular works are built up form new or used found objects, so, on some level at least, the art making process could be interpreted as reaction to the obsessive mass production of things that, when their uselessness become apparent, are wastefully discarded. Ultimately though, it is my contention that the obsessive processes involved in modular sculpture resonate on the level of our eternal questing to understand the structure of and meaning of things. As the material assumes a new form through the act of making, both sculptor and viewer discover new contents and suggestions. We adopt the stance of scientist or anthropologist as the specimen before us is dissected down to its most elemental parts; atom, molecule, cell, unit, component and building block. All are examined minutely, before the object is rebuilt and considered in its entirety. It becomes clear that these works, whilst generally not representational or metaphorical, brim over with meaning. These objects are never mute. Cooper,D. 2001. Tom Friedman. Phaidon Press:London Da Salvo, D. 2005. Open Systems: Rethinking Art.c. 1970. Tate Publishing:London Gragg,T. 2006. Tony Cragg:In and Out of Material. Verlag der Buchhandlung Walter König:Germany. Froud, G. 2008. Unpublished dissertation, Faculty of art, Design and Arhitecture, University of Johannesburg.

| |

Website of South African Artists |

|